Interview with photographer Nick Kozak

The images by Nick Kozak featured in the Color exhibition this month are part of a series called Peetabeck. His project started in 2015 with his first trip to the remote First Nation community of Fort Albany, Canada on the James Bay coast. Influenced by photographers like Jonas Bendiksen and Maciej Dakowicz, Kozak finds inspiration from their vision, as well as learning to take chances. Kozak says, “The people in my photographs are what really inspire me though.”

In our conversation, I asked Nick Kozak about his work with some of Canada’s First Nations communities, and what the work means to him, as well as the people he photographs. Kozak replied, “One thing I’ve learned in my time connecting with First Nations in Canada and Native Americans at Standing Rock is that family is very important. It does not just mean blood relations, but the idea of a community of people looking out for each other. When I photograph the individual it is often a reminder of how alone we can feel in the world and how important it is to be understood and connect to others around us.”

The idea of a universal perspective is one that Kozak embraces. “On a universal level,” Kozak said, “I hope it reminds us of all of our humanity by transporting the viewer into the world of those photographed. In terms of a personal level, I think that when someone looks at a strong image of mine they can on some level relate to the person or people in the images, can almost feel what they are feeling.”

“I photograph because I aspire to share the things I see and the experiences I get to have,” Kozak continued. “I’m not much of a writer and yet I have a passion for storytelling and sharing the world around me with others. I’m captivated by the fact that not all of us have the ability, time, or desire to connect with far off communities or marginalized people, yet we all benefit from knowing their stories.”

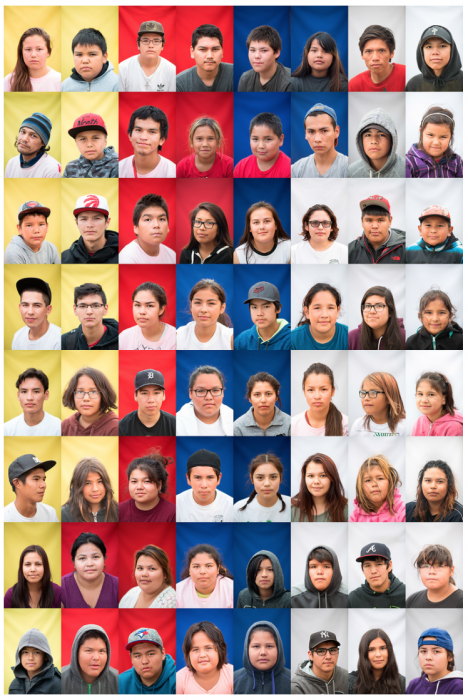

Thinking in terms of Kozak’s decision to shoot this work in color, we talked over the decision photographers make to shoot black and white in the classic, traditional style of photojournalism, and what makes his use of color important? After a thoughtful exchange of ideas, Kozak presented his approach. “There are definitely images in my series that could work in black and white, but then there are others I simply cannot imagine without colour. Take for instance, my image which is a montage of portraits on different coloured backgrounds (the colours represent the four colours of the Medicine Wheel, which is a very important tradition in First Nation culture). I definitely think the work would be less appreciated in color. Another example is the image called Nicole where we see Nicole Sutherland in stride wearing a red dress surrounded by a beautiful green natural setting. If nothing else there is the obvious complimentary color dynamic of red and green. As I think about the question of Color more and more, I realize that I absolutely always see the world in color. It may be simplistic, but that tends to be more important to me than textures or contrast that would be emphasized in black and white.”

When we talked about the obligations that photographers, or specifically photojournalists, may hold themselves to when working on projects like Peetabeck, Kozak replied, “I’ve always been very concerned with how the people in my photographs view me and what I do. I believe I have to be as open as possible with people and share my intentions as they come. I’m not 100% sure what I’m doing all the time but I know when I’m drawn to a story. I have an obligation to portray the people in my photographs with dignity whilst respecting the story and staying true to journalistic ethics. I have to respect the relationship I have with people who make me feel so welcome in their lives. Whenever possible I need to explain to people what my photographs are made to do and attend to any concerns they may have. I always hope that people feel like they have gained something from the process. Once the image is out there I think you can tell if the photographer has worked to get a photograph; whether they’ve been honest.”

Kozak summed up his approach to working on his projects this way, “I’ve learned over time that I’m not just taking a picture, I’m doing what I can to connect with the person, story, and environment in order to transmit meaning and truth about all of the above. Whether it’s labeled a portrait or a documentary photograph, I have the same hopes and expectations from both.

The more I photograph the more I realize the necessity of making a connection with the person or people in my photographs. I think a lot of photographers are eager to just click the shutter, but the real challenge is holding off and getting to a point where it’s just right, where the elements, both technical and the ‘je ne sais quoi’ align.”

Nick Kozak is a freelance photojournalist whose current work is focused on the issues of community and identity, their inseparability and constant state of flux. He explores communities that are displaced, marginalized, and/or those carving out new social spaces out of necessity or a desire to redefine a collective identity. His curiosity is combined with a keen eye, innate sensitivity and desire for greater social awareness. By nurturing relationships with communities and placing a great importance on learning from the people he photographs, Nick is able to create intimate pictures that tell informative stories.

Nick’s work has been supported by the Toronto Arts Council and exhibited in Canada, the United Kingdom, China, Poland, Bangladesh, and the United States. Nick’s editorial clients include the Toronto Star, Maclean’s Magazine, Toronto Life, Postmedia, Report on Business Magazine, University of Toronto Magazine, BBC Travel, La Presse, and Toronto Community News.

He has had major commissioned projects with Facing History and Ourselves, the Atkinson Foundation, and Evergreen City Works.

To see more work by Nick Kozak, visit his website at http://www.nickkozak.com All photographs © Nick Kozak. Used by permission.

Originally published at F-Stop Magazine.